Who is Michael Jang?

Season 26 Episode 19 | 41m 44sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

An elusive photographer uses street art tactics to share his previously unknown work with the world.

After a long career as a commercial and portrait photographer, mischievous San Francisco artist Michael Jang sat for decades on a hidden treasure of pictures taken in his 20s—both candid celebrity shots and a down-to-earth cross-section of Chinese American family life rarely captured so playfully. Then, during the pandemic, Jang set out to share his work with the world, street guerilla-style.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Who is Michael Jang?

Season 26 Episode 19 | 41m 44sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

After a long career as a commercial and portrait photographer, mischievous San Francisco artist Michael Jang sat for decades on a hidden treasure of pictures taken in his 20s—both candid celebrity shots and a down-to-earth cross-section of Chinese American family life rarely captured so playfully. Then, during the pandemic, Jang set out to share his work with the world, street guerilla-style.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Independent Lens

Independent Lens is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

How Public Libraries Make Lives Better

Books but more than books: From tax help and classes to borrowing random stuff, kids storytime, a place to stay cool, and much more, read about all the different ways public libraries can make our lives better.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipPart of These Collections

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship[Theme music playing] ♪ Man: This is a really interesting conceptual project because, in a way, I am enjoying and banking on my anonymity, and you're trying to expose it.

And what does that mean?

You may make a beautiful documentary, and people still won't know me.

That's very possible.

[Rock music playing] Man: ♪ Sometimes I feel like I [indistinct] ♪ ♪ Sometimes I feel like I will fade away ♪ ♪ Oh, sometimes high, sometimes low ♪ ♪ Just my life, a life you'll never know ♪ ♪ But if you want it, I'm gonna tell you ♪ ♪ You gotta know ♪ ♪ My life will [indistinct] for too bad ♪ ♪ But there's no place for more ♪ ♪ And you can cry for me ♪ ♪ 'Cause I know my life's starting too short ♪ ♪ Uhh!

♪ ♪ [Wheels clacking] Man: Hi there.

My name is Michael Jang.

Man: What's up, Michael?

Jang: And I'm an artist, and I've been posting around Chinatown.

I don't know if you've seen my black-and-white pictures of my Asian family.

Man: Michael has a big love for the world, and he has this-- this way of expressing it that's very unique.

Jang: What we're gonna do is-- we know we're right next to the police station, but we want to put one up right here.

Man: I think he really comes alive under the spotlight.

Secretly, that's always where he wanted to be.

Jang: I'm not afraid of what we're doing.

We're really supporting the neighborhood-- Officer: I mean, it's not really graffiti, is it?

Jang: No, it's not, so we're gonna roll.

OK?

Woman: There's a part of him that is a showman.

He's almost like a comedian.

And he's got these personas.

Woman: I was waiting to see who was putting these up in the neighborhood.

Jang: Can you tell-- No, can you tell us who's doing this?

Woman: That mischievousness in Michael's work is kind of his defining signature.

Who is Michael Jang?

You know, it's a question that you have to keep asking yourself as you see him shapeshifting.

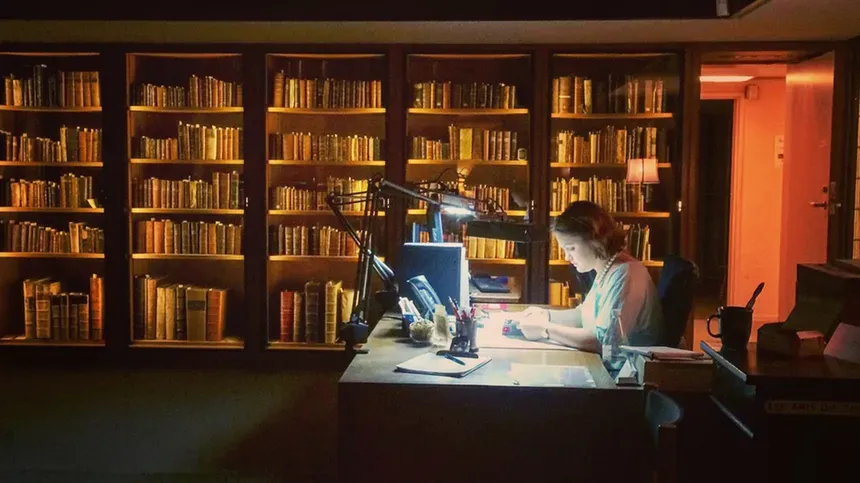

♪ Man: We are in the basement of Crown Point Press.

Our idea here is to do a pop-up show for a month and to bring Michael's work into a gallery.

I have no idea who buys this stuff.

I don't have any clients for this stuff, but I think formalizing it and, you know, taking it seriously makes you consider work differently, and I think it deserves that.

For artist who, you know, was a photographer a long time and how galleries looked at his work, the market looked at his work, kind of never really worked for him.

We're giving him something now.

You know, this is Michael Jang now, and we're here for the ride.

♪ Jang: I grew up in a small town in Northern California called Marysville, population 10,000.

It was,looking back, an an ideal "Leave it to Beaver" kind of experience, riding bicycles and shooting BB guns and going fishing.

And life was simple and nice then.

And my dad was always taking movies, always taking pictures.

So you kind of just grow up because that's what families do.

The first photograph I ever took is a picture of Willie Mays that I took at the then Candlestick Park when I was age 9.

And there was a door in outer right field.

So I planted myself there and as he approached, I just said, "Hey, Willie!"

And he looked up and I took a picture.

It was with a Brownie camera.

And I think maybe that was the beginning of it all.

♪ Woman: You know, Michael's work is very clean and there are candid snapshots, but they're so precisely timed that they could have been posed, and he did study with many new documentary greats-- so he studied with Winogrand.

His mentor was Lisette Model.

So, he is coming from within this canonic tradition of street photography, capturing the eccentric everyday.

Man: So it was something that Cartier-Bresson, the famous photographer, once described as the decisive moment which is capturing the essence of the event itself.

You are actively in that scene, and the shutter release is happening at the moment that you're seeing this thing unfold.

And I think that that's something that Michael's done so well over the years.

Woman: When you look back at the street photography that he made in San Francisco, he was everywhere that you would have wanted to be to make pictures, you know, so he had this uncanny sense of where to be, when to be there.

Man: The gorilla mask one, with a person in a bikini and--and the gorilla mask and the cop or the security guard, it was one of those images that really stuck.

Connor: I mean, the one of the bridge is so insane.

It's just a very unique picture.

And his sense of humor.

I'm remembering one picture he has of, you're on a cliff looking down at a beach, and I think there was a whole array of pigeons in the foreground.

I don't know.

The--he's just quirky.

[Film projector clicking] [Drum beating rhythmically] ♪ ♪ Jang: CalArts is where it all started.

I was in the design school because they didn't know where to put me.

I wasn't good enough to be a filmmaker or a painter or a musician.

So, "We'll put you in design."

Photography was simply an elective course, so I took it.

♪ I didn't even have a camera, but they had Leicas in the cage that you could check out.

I remember checking out a Leica and going into L.A.

I was at the Beverly Hilton Hotel, and I saw David Bowie out front, and I took two pictures and didn't think anything of it.

And then all the autograph people said, "Yeah, there's something happening here every week-- things like the Academy Awards, Golden Globes party for Frank Sinatra."

The paparazzi could only shoot that moment outside.

That wasn't gonna interest me.

I wanted to get inside, so I had to make fake press passes.

I would hear this all the time-- "The kid's here."

Ha ha ha ha!

I had no idea what I was doing, except that I was having fun sneaking in and taking pictures in a place that I shouldn't be.

♪ Connor: My first introduction to him was that Michael was a photographer and also really, really good at teaching Tai Chi.

Michael was a bit of an enigma, a little bit mysterious, pretty quiet, but you could just tell there was a lot going on inside.

He would challenge himself to do things, to get better at photography and to go outside his comfort zone.

He would just buy a bus ticket and just take bus routes, sort of all day long, and photograph out the bus as a kind of alert exercise.

How can I be challenged?

And how quick can I respond?

But when he was determined about something, I mean, he's very focused.

♪ Jang: If I had my druthers, I would just stay home.

Brian Wilson.

In my room.

I get overwhelmed, and I used to think that maybe that's why I took photographs.

Here's your frame-- top, bottom, left, right.

3 dimensions-- foreground, middle, back.

You have to see it all, make decisions on all those planes, and maybe even have something interesting in a second.

That takes a lot of concentration to do that.

So that calms me down.

When I go into a room, it's like having the white noise of a radio, as opposed to dialing down to just one station.

And the camera, by looking through, is like watching TV.

I used to say, "I'm kind of walking around just watching TV."

♪ Were there any art intentions?

No.

In fact, I had a hard time in art class during the critiques when I would put my pictures up and people liked them.

But then there's this funny thing they'd say.

"So what are you trying to do?"

I didn't have an answer for that.

And so because of that, I went through school feeling like not an artist because I didn't really have anything to say.

♪ Connor: I think I saw his potential, not as if he's gonna take New York by storm.

It was more that here was somebody who was working on his own... combination of things.

I remember discussions with him about what he was gonna do after graduation, and his plan was to have a studio to make some money that way.

As far as I knew following him, his commercial work was, you know, filling the refrigerator.

Jang: In the moment, I don't think you know what's happening.

You only get that perspective decades later, looking back.

I am Chinese, grew up in a Asian family, and generally speaking, don't be a nail because nails get hit down, so you don't make too much noise.

In most cases, people had a role model.

At the time, I couldn't think of any Asian or certainly Chinese photographers.

I'm not saying that's why I didn't keep going, but there's always the subconscious.

And maybe I just thought, "There's no place for me here."

And so I never pursued fine art photography after school.

That is why the pictures got boxed for decades.

♪ [Drums beating rhythmically] ♪ ♪ Man: Hmm.

Earliest memory...

I remember him decorating the house for the holidays, and I don't remember which holiday it was.

Maybe Halloween.

Halloween was always a big one.

He liked to make the house spooky.

Occasionally he would turn it into, like, a haunted house.

He was a very playful father.

Nothing was ever straightforward with him.

It was always like trying to figure out the hidden truth behind what he was doing.

I remember one time we came home, my sister and I, and we found him lying on the ground with ketchup all over his shirt.

And I think there was like a knife on the ground or something like that.

And that was a prank that he pulled on us.

And I thought it was funny.

My sister didn't.

Woman: The first memory of my father is so perfect, because it was a family photo shoot right there in the studio, at home.

Photography was always part of his life and part of his identity, and therefore a part of our family.

So we would be participants in it and we would also go along with him.

Interviewer: When did you first become aware that your father was a serious photographer?

Not until I was much older.

- This is the look I want.

Woody: While he was raising us, he was mostly focused on just earning money as a portrait photographer to support us, and he was doing less of his serious art.

It was easy for him to be overlooked for most of his life, both by himself, you know, and by the--the art world.

Jang: Hold this, and you're gonna just aim it at that thing.

You're gonna have your hand here.

There you go.

Woody: But I never got the sense that he was unhappy.

He managed to weave art into our life every day in some way.

So I think he was never creatively unfulfilled, because everything with him sort of turns into an art project.

Tali: It's really lovely to see pictures of people that I have personal memories with.

You know, spending Thanksgiving or Easter, Chinese New Year with these family members.

"Aunts and Uncles" is the photo that he took with his grandmother, my great-grandma, and her children and their spouses.

Seeing the joy in all their faces, I feel so happy looking at that.

And one thing that people don't see that I love is part of the story of this photo is my grandmother is on the edge and her arm's gesturing out.

She's looking at someone.

She's calling my grandpa to come in the photo-- my dad's dad, and I really like that part.

In the beginning, I just thought of them as, you know, ordinary family portraits because, you know, everybody has pictures of their family in albums and stuff like that.

I see them now as more as something unique and important.

Film narrator: On the very fringe of the shopping district is Chinatown, where the largest colony of Chinese outside of China lives its own life.

Here, the bazaars, street scenes, and architecture suddenly become truly Oriental.

Choh: I think you have to go back to American immigration history to understand the way that Michael portrays his subjects.

Photography came into being in the United States at the same time that all of these exclusion acts were enacted.

Prior to general passport requirements of identification photos, Chinese immigrants were the first group of people who were required to have their portraits taken.

There is a dark history of surveillance and government control, a lot of xenophobia and racism, unfortunately, but also a really interesting counter movement within that, too, where you can see individuals deciding how they want to self-style themselves.

Some people are dressed in more Western-style clothing that can signal kind of bourgeois respectability, or you see people choosing traditional Chinese dress.

You get more and more restrictions, but also more and more subversions, and Michael understands that because his family excelled, they thrived against really all odds.

[Film projector clicking] [The Martinels' "I Don't Care" playing] ♪ Woman: ♪ You said you're gonna leave me... ♪ Jang: I'm gonna be careful how I describe my family.

Ha!

They're still around!

I just want to say that it was a perfect storm.

Look, I'm a photography student.

I know the history of photography.

I have a Leica and a flash.

And this family was entertaining.

Woman: ♪ ...walk every day of the week ♪ Jang: My cousins, who are Jangs, I started just photographing them.

Took a little while for them to get used to it, but basically I just wore 'em down.

What image would you like to send to outer space to show life on Earth?

And that was the beginning of the Jangs.

Martinez: I think the entire Jang series is really compelling.

It's one of a kind.

I've never seen any other work like that, and certainly I've never seen a community represented like that.

Choh: His images feature a regular Chinese-American family with so much realness and normalcy, so much vivacity and dynamism.

And usually in medium, even today, you see mostly stereotypical representations, and this was completely different.

You know, his work is saying you don't have to be one or the other.

You can be both.

It's not about East versus West.

There's a mix and a mingling of all of these different cultural influences, and they exist perfectly together.

Woman: ♪ I don't care no more ♪ Chorus: ♪ I don't care no more ♪ Woman: ♪ No, I don't care no more ♪ Chorus: ♪ I don't care no more ♪ Woman: ♪ I don't care no more... ♪ Jang: Oh, here it is.

The date is January 14, 1978.

At that point in my life, I was out of school and needed to earn a living as a photographer, so I did everything-- Portraits, bar mitzvahs, weddings.

And in this particular morning, I had to be in the Miyako Hotel to photograph the employee-of-the-month.

The night before, Pistols had just played in their very last concert at Winterland, and I go into the hotel 10:00 in the morning with a Hasselblad and a strobe.

And I looked in and I said, I think that's Johnny Rotten sitting in the bar all by himself.

And he had like 5 beers and a bunch of cigarettes.

He told me the story.

He said, "We just broke up."

But anyway, I just said, "Hey, mind if I take some pictures?"

[Rock music playing] ♪ ♪ I was a photographer and at the time, it just felt wrong or pretentious to say, "I'm an artist."

I just kept shooting the way I always shot.

For instance, that series called "Summer Weather."

That was a job.

What had happened was a local TV station held a contest to be a weatherman for the summer.

Anybody could come in, and there were hundreds.

And I was hired to just catalog them, take one picture, get a name to 'em.

So I shot all these people, like one per person, and I put the film away for 20 years, and I found them, took them out and looked at them.

I had an assistant, a young kid.

I said, "What do you think of these?"

And he said, "Oh, yeah."

I said, "Are you sure?"

He said, "Oh, yeah, Michael, we need to look at these."

O'Toole: I remember very clearly the first time I saw Michael's work.

It was soon after I joined the museum, and he was coming to show us some work that he had made many, many years prior but hadn't really looked at for a long time.

Everybody's reaction at that moment was just awestruck.

We couldn't believe what we were seeing.

We were laughing.

We were just feeling like this work was totally unique.

The content was one thing, but it's also his great skill in terms of composition, in terms of timing.

We knew instantly that we wanted to acquire work for the collection.

Joo: In the history of the open call at SFMoMA, which the photography department, you know, famously has always had this--this opportunity for people to send in their photographs and be reviewed by curators, the only artist, or at least the first artist who was ever acquired was Michael Jang.

Woody: I remember like, the first time he ever had a photo on display at the MoMA.

He just took us there for fun to look at, you know, the exhibits.

Tali: I thought he was just taking my brother and me out for a day at the museum.

Woody: He didn't even tell us it was gonna be there, and we thought it was fake.

We thought he was fooling us.

We thought it was like a prank that he was pulling on us.

And he's like, "You know, that's actually my-- "that's my photo hanging up here, you know, in the MoMA."

We see one of his photographs, and our minds are blown.

And my first question was, "How did you do this?

How did you trick us?"

But he didn't.

It was real.

[Vehicle engine chugging] [Rock music playing] ♪ ♪ [Singers shouting indistinctly] ♪ - All right.

- Well, you've got this.

Boom, boom.

Yeah, yeah.

Boom, boom.

Right.

- Ha ha!

Man: To me, the connection between San Francisco, Michael, and skateboarding here, for us, it's like going against the grain, doing something that you might not be permitted to do but you know it's important and you want to capture it with Michael.

Clearly, it's like--it's a raw thing.

This guy just never gave up, really, which is, I think, like something that also relates to skateboarding.

I mean, you can skate your whole life and never get anything out of it, but you keep doing it because you love it so much.

And I think like, that's what would have happened with Michael, whether he got notoriety or not, he would have kept doing cool things.

So it's a really beautiful, close connection.

[Wheels scratching on pavement] [Drum beating rhythmically] ♪ [Sizzling] Hey, we're--we're opening in 10 minutes.

Yes, Chef.

Yes, Chef!

Brandon, hold on.

The tone is this.

"Yes, Chef."

OK?

A little lower.

Yeah.

"Yes, Chef."

Yes, Chef.

A little louder.

I need those dumplings ready right now.

All: Yes, Chef!

OK, you were late.

We'll try again.

Chop chop!

Interviewer: Where did you first come across the Chef Jang character?

I saw him on the streets of Chinatown.

I mean, I knew it was him.

His photos really resonated with me of just that Chinese-American experience of, like, how American our family life is.

That felt refreshing for me to be like, "I have felt this way for a long time, too," and that this exists between a lot of not only Chinese-Americans, but also, I think, immigrant American like families.

So I think like the feeling of it is--is very relatable.

- That's got to be gold.

- Ha ha ha!

♪ Martinez: Chef Jang.

Um, yeah.

I'm definitely familiar with Chef Jang.

I think it's--it's probably Michael's funniest character.

Michael's work has always had humor as a key component.

Chef Jang is just another aspect of that humor.

Coming out from behind the camera, the kind of effacing posture that the photographer has to, you know, occupy, you see Michael becoming an actor himself.

He's playing with something that's really relatable, but he's showing it in a new light, he's reclaiming it with so much joy, and he really skewers stereotypes.

He's poking fun at our expectations of who he can be.

[Papers rustling] Jang: As I got older, you know, I mean, I use a lot of pictures of me as a 20-year-old.

I said, "You know, to be fair, I have to kind of update things."

So I created this kind of alternate character so I could wear the chef's hat and dark glasses and the dirty cape and all that stuff, and gets back into mischief mode.

I think I need it to make it interesting for myself.

I don't know.

I think there's a lot of younger Asian people that would not go there just because, you know, things have to move forward.

And I don't care.

I think by operating with nothing to lose, there's no fear.

And having no fear in anything is one of the key things to getting something out there and done.

And so better late than never.

Woman: I met Michael because I moved into a studio showroom about a block and a half away from him.

He was in an unknown point of his career, but he had just gotten the recognition that he finally really deserved from the MoMA, and he was in their permanent collection, and he really had a lot of interesting things starting to happen.

Wattis: A friend of mine did a show of Michael's work and we were blown away.

There was some of the images of his work in L.A., there was work that showed his family.

It was his life experience.

And you were really kind of let in, and that was the extent of it.

I really liked it, and I even thought, "Wow, this would be great.

A museum or something should acquire this archive."

♪ O'Toole: I don't understand why people didn't just automatically think that these pictures were brilliant.

Maybe people underestimate work that's humorous.

People kind of assume that if it's funny, it's easy, but that's not really the case.

And the thing about Michael's work, you know, they're not one-liners.

They're complex.

There's nuance to them, but you may not necessarily see that at first blush.

From very early on, when I had any ability to speak to anybody at another institution or a publisher.

I would say, "You should look at this."

And a lot of people didn't listen to me for a long time.

Jang: Photography, when I first started in the seventies, you made a small print and it was 8x10 'cause that's all you could afford to make back then.

And the way you presented photography was white mat in a little frame on a white wall.

Why should I stay in that mode?

I need to do something different.

I thought, "Well, I'm not getting shows at galleries or museums, so I want to keep working."

I did not want to be a casualty.

Martinez: The very first time that I remember Michael doing anything kind of that big scale was this mural of a portrait of Robin Williams.

I forget if we had permission or not, but we installed this large mural and it was met with some surprise.

And folks were really excited.

Some folks, you know, weren't so excited, and that was kind of the catalyst.

Bluh: Like, you know when you're in the middle of something, it's like watching water boil.

So, like, I didn't even notice the gravitas of the movement that was happening, and then it just...ballooned.

Joo: One of the things that's interesting about it is that it's a new form for him.

So I think it shows that he himself wanted to challenge his own methods.

That's the part that's really unique, of course, not that somebody's working on the street, but that somebody who never worked on the street, who actually had quite a formal professional practice, then goes to the street and is like, "Let me meet people where they are in a different way."

Martinez: What's really distinct about it is that he's placing these photographs, photographs which themselves are highly coveted, collected in museums, regarded as fine art out in the street for the public to enjoy, to see, to interact with, destroy, you know, collaborate with-- whatever it is.

They have their own life out in the street.

Jang: When I first was just doing photography, people would ask, "Who were your influences?"

And I would say, "Well, Leonard Winograd and Diane Arbus."

50 years later, if someone were to say, "Who are you looking at now?"

I would say Warhol and Haring and Basquiat.

You know, if you can be more playful and less technical, it's more human.

I will think of a theme like Chinese hats or Chinese cigarettes or vintage toys and just--just Google search images, and then all the stuff pops up.

Interviewer: Yeah, you had mentioned like, "Hey, you know, if Warhol had the Internet, right?"

Jang: Well, again, but it gets back to Warhol's not Chinese.

So when I'm in Chinatown, I throw these little dimsum treats at them because they appreciate it.

[Spray paint ball rattles] [Paint hissing] The average person who lives in Chinatown going to the market every day, they just see them and kind of go, "What is this?"

But they like it.

Almost every neighborhood, man, it gets tagged, torn down within weeks.

But some of the stuff has been up for 6 months.

So that's the one reason why I keep going back.

I mean, if I wasn't wanted, I wouldn't go back.

♪ Wattis: We got into the pandemic and of course, life changed.

Museums were closed.

No one was going around.

And all of a sudden there was this big plywood wall where the Goodwill was.

And on this plywood wall would appear these paste-ups.

They were really cool, and I'd recognize some of the images, and I kind of put 2 and 2 together and it was like, "Hey, that's Michael Jang."

It became part of the pandemic experience, and it was a breath of fresh air.

Joo: Certainly during the closures due to the pandemic and the resulting anti-Asian violence that we were experiencing here in--across the country, when this tone became really pronounced, you know, to see Michael's intervention was really meaningful, and I thought, you know, this is something, you know, at a different level.

O'Toole: I knew that he was going to post on the Great Highway, so I rode my bike down to look for the Jangs.

And I just loved seeing people stop and, you know, take a double take.

He was doing exactly the kind of thing that--that was meaningful at that moment.

[People talking indistinctly] Jang: I thought, all you have to do is see what's happening to people now on the streets and stuff.

♪ Luckily, I feel like these images that I made 50 years ago, the content is still interesting and captivates people.

It has relevance now in a way that I couldn't have ever hoped for.

Joo: I know that, you know, Michael doesn't want his work pigeonholed into something that's purely Asian-American, but I think, you know, neither can we have our subject position denied.

So I think it's a tightrope of a lot of assumption and stereotype that Asians in America deal with daily.

And so then you get this guy, you know, this curious, humorous, slightly anarchic guy... [Fireworks crackling] you know, just inserting himself everywhere.

"Yes, I see you and I hear you."

And these were really powerful gestures at that time.

They really moved me.

And I think that's when we knew that we should do something with that at the museum.

Jang: Let's take a look at it.

I don't know if glass is gonna fly.

It's too reflective, right?

[Paper ripping] See this?

This is gonna go, like, right up on the ceiling there.

This is the hot zone.

So, a little high.

Probably a little higher, and shade it toward Elvis.

Martinez: Working with Michael, it's a fun adventure.

He is very in tune with how he wants things to turn out.

And I think that you have to give him space to express that.

You know, like any project, the trying moments where you're trying to figure things out and navigate challenges, it's always gonna be tricky, but I've learned to appreciate that as well, because I understand that Michael's vulnerability is part of what gets him to that result that's so compelling and, to be quite frank, so excellent in many ways.

Jang: OK, so we're getting there.

By the time we get to the end, it'll be-- We'll have it figured out.

Ha ha ha!

Bluh: I describe him as an artistic, creative genius who is atypical.

I mean, I'll be really honest.

It's been a difficult road.

You expect certain themes in interactions with somebody, and Michael doesn't always recognize those normal cues.

So, it took a lot of me trying to understand the way he worked, and then, um, to be really honest, I made him get diagnosed.

♪ We don't use the--the words like "autism" or what's the other one, "Asperger's" or whatever.

We don't use that.

But when you're a little kid growing up in the fifties and you know, you're riding in the car and you look out the window and you have to tap your foot every time you pass a house and see the door.

When I think back on it now, I go, "Oh, there you go, right?"

So, whatever it is, whatever you want to call it, it hasn't gotten in the way.

It is a gift that I know how to use to my advantage.

I can pick up a camera and make a picture in my mind and will it to happen.

You know, there's that self-portrait when you look through the camera, and there's, like, 6 people all the way across that image just perfectly in place.

What is that?

I think I might be wired a certain way to be able to do that-- just saying.

♪ How am I feeling?

There's--there's a lot of emotions.

You know, there's relief, but there's also elation.

And, you know--you know, sometimes there's sadness because...it's my family, and a lot of them are no longer here.

So while this all looks really fun and happy, and I know it is, it's also--there's a price to pay for it.

This is issued at the Port of Entry in San Francisco.

The date is 1923.

Want me to do the math on that?

We're at the 100-year point, and there's been a lot that's happened in the last 100 years, from this to what my father went through in the Depression to the life I was able to have as a free-range kid in this country.

I did anything I wanted to do, and I still am.

Ha ha ha!

♪ Woody: I'm really happy that he is, you know, finally getting the recognition that he deserves as an artist.

I think we've traded places.

You know, when I was younger, he was watching me develop, you know, and chase my dreams.

And now I feel like I'm watching him do the same.

Tali: He is bringing so much of himself and his own identity and his own interests into his art.

I think I'm really happy to see that he's still driven to put more art into the world.

Ultimately, I think that's a great thing.

O'Toole: Having seen the arc of how his late-stage career has gone is super-exciting and I just couldn't be happier for him and happier for the fact that more people know this work, because I have hoped for that for a long time.

Martinez: Michael's not necessarily out there making pictures right now, but he's using the pictures in a different way.

He's using the content.

He's interacting.

He's absolutely making art.

There's so many different Michaels to be seen, whether it's from the art world, whether it's from the commercial photography side, whether it's just from San Francisco or even skateboarders now.

What he's doing is really expressing himself in totality, and I think that that's really compelling for folks.

Jang: I don't care that it's taken 50 years.

It's delayed gratification.

Right now, I'm just like starting.

I've been encouraged, and you got to be careful if you encourage me-- ha ha--what I might do!

So, yeah, I'm riding that wave.

[Rock music playing] ♪ ♪ Keep off my shadow ♪ ♪ Don't drink my beer ♪ ♪ It's a risky city ♪ ♪ We're all strangers here ♪ ♪ Don't catch my eye ♪ ♪ Don't walk across the sky-y-y ♪ ♪ In a risky city ♪ ♪ For that, you might die ♪ ♪ It's a risky city ♪ ♪ Bright lights are there ♪ ♪ It's a risky city ♪ ♪ Bright lights are there ♪ ♪ Say yeah ♪ ♪ [Film projector clicking] ♪ ♪

Trailer | Who Is Michael Jang?

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S26 Ep19 | 30s | An elusive photographer uses street art tactics to share his previously unknown work with the world. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by: